Author: Keith W

Settling into Winter

We still have Turkeys available for Thanksgiving dinners, along with beats, brussels sprouts and chickens. Stop by the Farm anytime, text, call, or send a message on our socials for more info.

We are a month from the solstice and I can still find tufts of grass and kick at frozen dirt on my way across the yard, but the animals are in the barn each night and as I am writing this it’s been dark for hours. As far as I’m concerned, it’s winter on the Farm.

The Farm runs on routines. After my coffee, I walk to the barn and hit the first light switch. Steel scrapes concrete far down the aisle as Chippy gets his shoes under him and abruptly stands, looking embarrassed that I caught him laying down. His mane and forelock are covered in shavings, a horse’s version of bedhead that leaves no doubt he was out cold. As I travel through the barn Wilbur grunts and stirs in his nest, but doesn’t bother getting up. I hear the shaking of dog tags as Benny and Tuffi’s bleary eyed faces peer out from the main stall gate. They’ve been up all night patrolling fence lines, and are waiting on breakfast before napping in the sun most of the day. Chippy begins to talk, a rumble from deep down, as if clearing his throat to remind me he wants his oats. Jewels and Leroy hang their long faces over their gates, thinking the same but letting Chippy do their talking for them.

I start with the horses. As water spills into their buckets, I appreciate that the hose hasn’t frozen in spite of the 24-degree outside temperature. Soon enough my routine will include hauling buckets 100′ down the barn from the water hydrant. I cut bailing twine, releasing three bales of hay and leafing it into each horse’s hay box, followed by the goats’ feeders. The dogs get there breakfast too, Benny in the aisle and Tuffi in the main stall. If Benny so much as looks at Tuffi while she’s still eating she will attack, so he eats separately for his own protection. Just another routine. As I grab the steel grain scoop I feel its chill through my gloves and dig into the hog feed. The sounds is Wilbur’s que that it’s finally worth getting up. He is scratching his backside on the gate as I pull up on the latch. I dump the scoopful into his trough and rub his back as he noses into his grain.

“Morning Chippy,” “Good girl Jewelsy,” “Oh Leeeeroy,” “Macky and Jacky,” “Hello Ladies,” “Wilby,” I chat it up with everyone as I make my rounds. I pet noses, scratch between horns and give a tail a friendly tug. Eventually I head out the door, forced to confront that I have a day away from the farm awaiting me. A faint orange glow is rising to the east over the back fields, pushing up on the darkness. The snow, ice and dirt crunch under my boots as I head down the driveway, start my work truck and head back into the house to pack my lunch. Liz is coming down the stairs. She has her book and sits in the rocking chair by the woodstove which I stoked on my way out the door. She’ll relax for 30 minutes— it might be the last time she sits today. Shortly after I pull out of the driveway she will head to the barn and start her own morning routine; turning the horses onto pasture,, tending to the laying hens, milking the goats and bringing grain to the pigs that are still out back. She’s off and running.

In the evening, the three of us will convene back in the barn, arriving like bees returning to our hive after a busy day. Ellie’s days are spent at school, and once off the bus she will either decompress in quiet independence behind a book or shadow Liz with a series of questions, request and stories, at times offering her ‘assistance’. Liz does everything for the Farm all day. She is the manager, laborer, accountant, banker, store clerk and many other hats 365 days a year. She only breaks away when its time to lend a hand to our community, which is as much a part of having a small farm as farming. I spend 4-days per week in Baxter Park, supporting the Farm in a more indirect yet necessary way, which is to say providing capital cashflow.

Once the three of us are in the barn and the darkness pushes the orange glow down behind the Mountain to the West, the temperature sinks along with it. The three of us get to work, although its the kind of work that’s not work, at least not in the negative sense most think of it. There is no drudgery with this work.

“But is work something we have a right to escape? And can we escape it with impunity? We are probably the first entire people ever to think so. All the ancient wisdom that has come down to us counsels otherwise. It tells us that work is necessary to us, as much a part of our condition as mortality; that good work is our salvation and our joy; that shoddy or dishonest or self-serving work is our curse and our doom. We have tried to escape the sweat and sorrow promised in Genesis–only to find that, in order to do so, we must forswear love and excellence, health and joy.” Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America

As Liz cleans a horse stall, Ellie marches into the pasture, calling to the horses and leading them in for their dinner. The goat flock is in and out of their always-open door, banging horns, pushing and sorting out their ever evolving social order which is at peak volatility during fall. It’s breeding season. The bucks are in their own stalls, standing with front feet on gate rails waiting on either grain or a doe in heat. I scoop Wilbur’s dinner into his trough. At the other end of the barn we can hear the chickens sorting out their own order with frequent wing flapping and an occasional squawk as they rise to their roosts and sort out positioning. Us three talk a little as we work, about Ellie’s school day and what she did in art class. About our neighbors. whether Joe stopped for goat milk for his baby sister, or if Menno has gotten his deer. We check in on which of us has done what chore, and who still needs to be fed. I dig a scoop into the goat grain “I’ve already fed the boys” Liz says from over a stall wall. I move on and search for the next task. “The pigs up the hill still need fed; the grains already in the side-by-side.”

When the necessary chores are done, are activities become more social and discretionary. Liz and Ellie brush Chip, while I visit with Leroy and Jewels. I move on and start leisurely shifting hay from the storage stall, to below the horse feeders in preparation for morning chores. Ellie puts her goat Tiny on a leash and walks her into the aisle. Liz joins them with Chippy, lifting his front hoof and picking mud and ice from its crevices and around his shoe. The task catches Ellie’s eye and she puts Tiny back in the stall and joins her. I move to the other end of the barn, put our chainsaw into the benchtop vice, and start blowing out the frozen woodchips and dirt collected under the clutch cover from cutting the weekend before.

As I begin sharpening the saw, Ellie joins me. Liz has gone to the house to start dinner so Ellie and I begin a lesson on chainsaw sharpening, a skill close to my heart. We talk about the angle of sharpening, and how the file guide helps you find that correct angle. We discuss why the teeth alternate from one side of the chain to the other. I point out the rakers and how they guide the depth of the chains cut. I was almost 30 years old before I knew how a chainsaw was sharpened, and know grown men who will buy a new chain before sharpening a dull one. I tell her maybe one day she will teach her husband how to properly sharpen her saw.

It’s Thursday night. For the next 6 months, this will be every night. The darkness outside, the frequent winds and soon to arrive snow, push us to the confines of the barn, 40′ by 140′. In the barn we are sheltered, and focused. The barn blocks our signals to the outside world. Everything we need is there. We are closer to the animals in the winter. It feels as though they need us—we surely need them. Eventually, Ellie and I turn off the last barn lights, pull down the door and slip down the driveway to the house.

On Butchering Day & Community Food

The Miller Family rarely travels as one. I assume this is a result of enjoying their home, and also because a crew that includes 9 littles spread across the last 10 years is tough to get out the door. We know when they travel, since they pass our Farm to get about anywhere, and often borrow our horsepower. It’s Church every-other Sunday, a few social trips a year and butchering days here at the Farm—the latter outnumbering the former.

Up at the killing area, Menno and I find a steady rhythm of kill, scald and pluck, with me swapping between wielding the knife and running the plucker while Menno dunks each bird into the 154-degree scald bath. Liz, Mary and the Lydia, Menno’s niece from New York who is here as the teacher at their schoolhouse, setup shop in our dooryard outside the Farm Kitchen. Here, they handle the evisceration, before moving inside for final cleaning, packaging, and labeling.

The children fan out, balancing play with finding tasks and being found for others. Mose, with ear tips pink below the brim of his hat, pounces on an escaped bird. Becky reaches into the ice water filled barrel, pulls a chicken out by its leg and uses the weight of the bird to flex the leg joint and cut away the foot which she tosses into a bucket for Liz to turn to stock. Once plucked chickens need transport down the hill for further processing. We call in the cavalry and Ellie, Lydia*, Maddie, Katie, Andy and the others previously mentioned come running, grabbing one or two handfuls of chicken leg each and running the now naked birds down the hill where their short journey from field to freezer will be completed. Sometimes I’ll watch as they trudge back up the hill with a grin on their faces as if pulling sleds in anticipation of another toboggan run, only their reward is another handful of chicken to transport. It doesn’t seen to make a difference to them. Sometimes, they disappear and I find out later they were taking turns warming themselves in the boiler room.

*Menno’s oldest daughter, not the niece/school teacher. Same names make Amish a challenge to write about. I suspect there’s purpose behind this; something I may work into my writing some other time.

Reflecting on the help and play of the Children brings to mind a quote from Wendell Barry’s writing which I will share below. If you are unfamiliar with Barry, you can start getting to know him in this article. I’ll quote him often as his writing (which I’ve been devouring as of late) is an inspiration and puts the work of small scale farming, and much more, into words better than most anyone.

From his Essay Economy and Pleasure first found his collection of essays What are People For.

On many days we have had somebody’s child or somebody’s children with us, playing in the barn or around the patch while we worked, and these have been our best days. One of the most regrettable things about the industrialization of work is the segregation of children. As industrial work excludes the dead by social mobility and technological change, it excludes children by haste and danger. The small scale and the handwork of our tobacco cutting permit margins both temporal and spatial that accommodate the play of children. The children play at the grownups’ work, as well as at their own play. In their play the children learn to work; they learn to know their elders and their country. And the presence of playing children means invariably that the grown-ups play too from time to time.

It’s worth noting that if it weren’t for the help of the Children, we’d be using the tractor. Once out of the plucker, chickens would go into ice water, a plastic barrel on a pallet transported down the hill on the forks of the tractor 20 or so birds at a time. The technology is not an improvement.

Butchering days start after dark the night before with the gathering and crating of chickens in the field. It begins again before sunrise the morning of as one of us heads out coffee still in hand to fill scalder and start it warming before we hustle through morning chores with a little more urgency than usual. Once the main task is done, there’s cleanup and disinfecting, equipment to put away, offal and feathers to stir into the compost, stock to simmer and can, evening chores, and if we’re lucky a hot dinner and warm shower before bed. Ok, definitely a shower before bed. This is all to say that butchering day is a full day, that spills into the day before and the day after. Liz, Ellie and I could not do it without help and in our 10 years of raising chickens for the table, we’ve never been without the best help. These helpers and the aura of community coming together to lend a hand for local food, make these days some of my favorite of the year.

Kill, scald and pluck, Menno and I discussions drift along like the clouds overhead in the cold November breeze. We of course discuss the chickens— how this round appears smaller . We speculate on the reasons; the cold weather, the size of the group, the recent droughts effect on the pasture and the challenges of keeping fresh water unfrozen this late in the season. We talk about his portable sawmill on order, a much anticipated new endeavor for him. We look forward to finishing up our falls tasks in preparation for winter, freeing us to do other pleasurable work, most notably taking our horse teams into our woodlots to harvest sawlogs to feed his new mill. I find out that it’s the Twins’ (Maddie and Mose) 8th Birthday, and I make sure to give them each well wishes as I hand them the gift of more chickens to run next time they arrive up the hill. Once they are off Menno sighs, and remarks that this day is almost identical to the day they were born. I can tell he is searching for words as he says little without thought. Finally he finds them and shares what a blessing it was, having healthy twins born at home on a beautiful late fall day with no complications. We continue; kill, scald, pluck.

Once the chickens are all down the hill, we move to the Turkey’s. Much larger, their strength is hard to contain in death and we work together to restrain their wings after the death blow is delivered. Two grown men, shoulder to shoulder, straining to restrain the birds in their final moment feels as personal a connection to the process of one’s food as you can get. It’s not fun, but necessary as the stainless steel cones used for the chickens aren’t nearly large enough. We discuss investing in larger cones for the Turkey’s, a likely purchase for next year if our trial run of Turkey’s for this Thanksgiving is deemed a success. I realize this may be a graphic description of the process, but I take pride in the humanity of it and the fact that our process still resembles agriculture, as opposed to the industry of .99 cent per pound factory Turkey’s mass produced by global organizations.

We move the Turkey’s down to the dooryard for gutting. Liz, Mary and Lydia the school teacher, have moved into the Farm kitchen where they are packaging the last of the chickens. As the last of the birds to reach the freezer, they stand on the porch for a break as Menno and I begin gutting the turkeys. “You men are slow. We’re waiting on you.” Mary quips. “Our job is done, they’re all killed and plucked,” I shoot back. Menno adds that we’re doing their job now. The banter continues and even Lydia the school teacher, a young newcomer to our unique group, joins and tells us that the women have been doing two jobs, gutting and packaging, to the men’s one. I count kill, scald and pluck as three tasks while pointing out that the men have been outnumbered two adults to their three as the teasing devolves to the women counting the removal of each organ as an individual task.

Eventually, I send Ellie to the barn followed by a group of her friends, the Miller kids, to get our horse Chip in from the pasture. Menno and Mary will be taking Chip this afternoon for an errand to town, leaving their horse in our barn from some needed rest while giving Chip some good work. Once they’re gone, Liz and I finish cleaning up and begin tidying the Farm for upcoming snow.

My shadow is long in the pasture as I roll portable fence rope and pull fiberglass posts from the ground, disassembling the chicken pasture as we are done with meat birds for the season. I pull turkey feet from my pockets and toss them to the farm dogs, a chewy treat and reward for keeping the livestock safe. My back is to the road as I hear the familiar clip-clop of hooves echoing from up the road. I turn and see Menno’s head leaning from his buggy, his face covered by the brim of his hate as a hand reaches out in a wave while the other holds the reigns tied to our horse. Having delivered the school teacher and children home, he and Mary are off and their errand. They won’t be back until well after dark, when they’ll swap our horse for theirs in the barn before their final 2-mile trot for home.

From Wendall Barry’s 1988 Iowa Humanities Lecture, The Work of Local Culture.

A good community, as we know, insures itself by trust, by good faith and good will, by mutual help. A good community, in other words, is a good local economy. It depends upon itself for many of its essential needs and is thus shaped, so to speak, from the inside—unlike most modern populations that depend upon distant purchases for almost everything, and are thus shaped from the outside by the purposes and the influence of salesmen.

If you’ve reach this far, I suppose I will let you know that we do have turkeys, chickens and other food from the Farm for sale here at the Farm. Stop in and see us anytime, or send us a note on one of our socials to make arrangements.

Allagash 2021

There was no sound. Liz and I both remarked about the strange ringing in our ears created by the complete dearth of noise. It was exactly what we needed.

The last month had undoubtedly been the most challenging in our 5-years of marriage. We were as strong as ever, but life had been piling on for weeks. Don’t get me wrong, as a family, we are extremely fortunate. We are well employed, have a beautiful property, amazing support around us, an incredible healthy child, and the list could go on. But the sudden illness and passing of Liz’s father, our goat flock going missing for two days and the subsequent (successful) search, some tractor issues, and more, all hit when the busyness of the farm was getting a bit more than we like, the stress of our day jobs was high and prepping the farm for this very trip was peaking. We were worn out and desperate for a break.

All that noise of life, made the moment, the complete silence, remarkable. The headwater lakes of the Allagash are large, and frequent winds can make crossing them treacherous. On our first Allagash trip in 2016 (pre-Ellie), we were forced to take a zero-day due to roaring headwinds and crashing white-capped waves preventing any forward progress. Not today though. As we headed across Churchill Lake on our second day, the water had a slight ripple, but nothing more. The Allagash is isolated, stretching across the scarcely populated Northwest quarter of Maine, but it’s not without human effect. Logging operations are always hidden just out of sight of the Waterway, airline flight paths criss-cross overhead and canoes with outboard motors are permitted on certain lakes with restrictions. Still, there was no sound. No wind or waves, no trucks or planes, no motors, no people, and most surprisingly in this case, not even the quack of a duck or cry of a loon. Even Ellie sat quietly. We had made it.

For a few weeks in August, it didn’t seem like we’d make it to the Allagash. Even the Guide Service that was supposed to shuttle our truck from put-in to take-out, an important piece of logistics for a river trip, canceled on us days before. Fortunately, but not without stress, we found a backup shuttler, and when the calendar hit the 21st, we were driving North before 7 am. We hit the Golden Road outside Millinocket and didn’t look back. After two more hours of driving, all on dusty dirt roads, we were at the put-in. Not unexpectedly a lack of rain in Northern Maine left Indian Stream, our 3/4 mile long access route from the parking area to Eagle Lake, with too little water for paddling. Just a minor inconvenience given the last month. We loaded the canoe and wadded down the stream dragging our trusty craft behind us. Finally, we made it to Eagle Lake, into the canoe, and were paddling.

The first day and a half felt like a giant exhale. Clear weather, calm waters, and no other paddlers to compete with for campsites allowed us to truly relax. We took a minor detour on the first day to show Ellie the trains of the Eagle Lake & West Branch Railroad, a little hat-tip to Grandpa George who was a train lover. Our first campsite on the North shore of Eagle Lake gave us perfect late-day sun, a nice gravely beach for swimming, and a perfect view to watch the full moon rise over the shore to the East.

The next morning after paddling from Eagle to Churchill Lake, crossings the latter, and reaching Churchill Dam, we ran the Chase Rapids. Generously described as a 9-mile long Class II section of Whitewater, it is not particularly challenging, but it still requires some reading of the water to find and maneuver through the best lines. The teamwork required for Liz and me to steer the canoe in whitewater is a testament to, and microcosm of, our relationship. Sitting in the stern, I do the majority of the steering, and while my water reading skills have vastly improved with Liz’s instruction, they are not as good as hers.

At times Liz will yell a warning “rock on the left” and I’ll rudder hard to the right, while she throws in a strong draw in the same direction as will slip by the hazard. Sometimes I’ll disagree with her warning, and she will trust my read and with a coordinated effort we guide the canoe down a smooth line. Often I will read Liz along with the water; I’ll see her throw a slight left draw into the beginning of a stroke, I’ll glance ahead at the water, see what her stroke is showing, and mirror her effort all without a word being said. Errors happen, either I read the water wrong and we bump our way down the river awkwardly, or I’ll follow bad advice from the bow with similar results. It happens.

The best mistake on this trip was when I told Liz we needed to go hard to the left, and she gave me a strong draw to help get us there. I immediately realized that I had meant to tell her to go right, and our efforts canceled each other as we plowed straight ahead. After we dislodged ourselves from the rock, Liz turned with her hands in the air “I didn’t know what you were thinking but just did what you said!” Whoops. I owned that mistake.

Ellie witnesses all this banter from her middle seat, a perspective from which I am sure our antics can sound a wee bit like a fight. She has learned to go with the flow, the whitewater, the yelling, the bumps, and waves. Her job is to yell “Woo Hoo,” anytime we ride smoothly over a good wave and through a rapid, a job equally important to ours. The three of us are an ok team. As we pulled into the eddy the marks the end of the Chase Rapids another canoe was just pushing away from shore; a father and teenage son presumably. The pair was soaking wet from head to toe. “You must know what you’re doing,” they said to us. “We flipped three times.”

While everyone loves white water, our favorite section of paddling is always the calmer waters that bring us into Round Pond later in the trip. Shortly after you cross under Henderson Bridge the river divides into several calm and shallow channels. Tall grass and shrubs line the banks which are dotted with majestic old-growth elm trees, a rarity in our time. Elms used to be a common tree in hardwood forests and a popular landscaping tree in cities and suburbs. However, the past few decades have seen almost all North American and European elms killed by the Dutch elm disease. While these Round Pond elms are scarred along their bases from violent ice flows, their isolation along the Allagash has sparred them from the pervasive Elm disease.

As we entered Round Pond on the third day of our trip. we found the Inlet campsite unoccupied, something that had not occurred on our three prior Allagash trips. We set up camp within sight of where the grassy, shallow, elm-lined channels enter the pond. As Ellie was waking up from her tent nap (first of the trip) I peered across the pond to the inlet channels through our monocular, a hand-me-down from Grandpa George. As I scanned the tall grasses I passed over a tree stump, only to find when I scanned back it was gone. When I found the stump again it was splashing along the shore with 8 moving legs—a Momma and baby moose. We quickly mobilized, tossing warm clothes on Ellie, buckling life jackets on the three of us, and sliding our canoe back into the water.

We could no longer see the pair of moose, but as we paddled quickly towards the inlet channel where they had been, we crossed the mouth of another inlet and saw a different one feeding in the shallows. We steered to our right and nosed our way upstream along the grassy shoreline and watched as the large female lifted her head out of the water chewing on fresh greens from below the surface. Even from a substantial distance, it was obvious she was well aware of our presence. Her ears were perked as she stared directly at us. We continued to keep our distance but after a short time, she decided she didn’t like to be watched while she ate and splashed her way to shore, out of site and into the bushes for privacy. We headed back into the pond and searched the next inlet for the Mom and Baby and we circled a grassy island we caught a fleeting glimpse as they slipped out of the water and into the woods.

Growing up in Maine and living in the White Mountains I’ve seen plenty of moose, but seeing them from a canoe on the Allagash was different. This was not a Pinkham Notch safari moose, or a Friday evening Kancamangus Highway chamber of commerce special. The shyness of these beasts proved it. The next morning we even got an encore. Liz, first from the tent, quickly returned to tells us “They’re back.”

As we paddled out of Round Pond later that morning, one of the two other groups we saw on our trip was enjoying breakfast at the outlet campsite. A young girl, smaller than Ellie, strolled down to the shore with her Mom trailing a short distance behind. “Hi Ellie,” the girl yelled with a wave. We had leapfrogged this group a few times, passing them in Long Lake a day earlier as they set up their camp in the afternoon. The young girls, Ellie and Audrey, had yelled introductions then and were continuing their pleasantries now. We learned that Audrey is three, a year younger than Ellie, and this was her second Allagash trip to Ellie’s third. I’d love to track this family down back in the real world. Perhaps Ellie could send Audrey a letter, as they seem to have a few things in common.

It’s fun to reflect on Ellie’s growth as a child relative to our previous canoe trips on the Allagash, Penobscot, and elsewhere. Our trips started before she was even a year old. I’d engineer a seat for her in the bow, facing Liz. There were various sun umbrellas and rain canopies along the way, some better than others. Now, we are worrying how much longer she will be content to sit in the middle seat as a passenger and not in the bow or stern where she can play a more important role. While she has begun to “help” in camp with tent setup, water filtering, and gear carrying, having a 4-year old on a river trip still adds greatly to the logistics. Her presence heightens our nerves in whitewater, and her attention span for long days in the boat needs to be a consideration. It is so incredibly worth it though; watching her excitement seeing the moose at Round Pond, her joy as she splashed in the shallows of multiple remote lake campsites, or her wonder as she creeps towards a cotton tail rabbit grazing in the grass near our tent. Her ability to join intelligent conversations, and ask smart questions about the natural world around us makes it all even more fun, even if she still needs to learn when Mom and Dad would like some quiet time in the canoe.

We set up camp on the last night of our trip at Allagash Falls, a violent 40-foot drop where the river cascades over upturned Seboomook slate. On previous trips, we’ve carried around these falls on the quarter-mile portage trail as a part of our last day on the river, but on this trip, we decided to camp at the falls and enjoy them a bit more. That evening we made camp along the portage trail, went for a swim below the falls, and explored on the ledges at its base.

For dinner, I cooked my go-to meal, pasta with prosciutto, artichoke hearts, dried tomatoes, and garlic. We sat on the riverbank facing upstream at sunset, celebrating and lamenting the near end of our trip. This portage and the falls is one of the busiest places along the 100-mile waterway as people load and unload boats for the portage and take in the sites of the falls. We had the landmark area all to ourselves though, and fell asleep listening to the roar of the falls.

Now, a few days removed from the Allagash it’s even more obvious that the trip was exactly what we needed. When we paddle together, Liz and I hit a rhythm that is hard to find elsewhere. Whether it’s crossing a lake with white-capped waves, paddling through rapids, or down a long section of calm river dead water, our minds wander away from our paddles which we instinctively move without thought, to other places usually locked away by real-world distractions at home. I always return from our trips motivated to slow down and take more time for important things.

Last night, with the canoe still on the racks of the truck, Ellie and I headed to Mountain Pond just a short drive from home in the White Mountain National Forest. I carried the canoe on my back down the 3/4 mile access trail, while Ellie led the way wearing her life jacket and carrying her fishing pole. We slipped the empty canoe into the calm waters and I paddled us around the pond while we both fished without a bite. As the sun got low, not wanting to be late for dinner, I coaxed Ellie to the back of the boat. As she stood with her back to me I squeezed my legs together and held her steady between my knees. I had her put one hand on the tee grip of the paddle, with mine over it, and the other a short ways down the shaft where I again, put mine over hers. Now, in the proper position, we paddled for home together.

I can’t write about this trip without acknowledging the assistance we had at home. A huge Thank You to Liz’s Mom Deb for watching over the farm as a whole, and to Brian Patry, Matt and Mouna Goyette, Dominique Dodge and Eric Koeppel, and Dan Kurnick for being expert goat milkers, animal feeders, and jacks of all trades to keep the farm going while we were gone. We would not be able to leave our home behind without the support of these special people.

Ready for Sugaring – 2021

To view our 2021 Maple Syrup prices click here. Send us an e-mail for ordering information. Stay tuned for additional Maple Products.

The recent dusting of snow has been a blank canvas for tracking the movement of small animals. Each step of a gray squirrel as it sprints to the next tree leaves a mark with little foot pads and claws. And while doing chores Sunday morning I was able to track a more rare small mammal that arrives as the weather begins to warm – an Ellie Bellied Sap Drinker. Sunday I found the animals small footprints circling a cluster of young maples, a sure sign that sap will be flowing soon.

The run up to the 2020 sugaring season was hectic. We were just putting the finishing touches on our sugar house as the woods began to thaw. This year our lines were in place and ready to tap in January, about the same time we were ordering our evaporator a year earlier. With a few 40 degree days forecast for this week, this weekend was “Go-Time” for the Dundee Ridge Farm 2021 sugaring season. On Friday we cleaned the bottler. We spent Saturday scrubbing the evaporator, having a test boil with water and organizing the sugar house. Sunday we trudged into the woods to tap the trees. Ellie and I drilled our first hole at 8:30am, and Liz, Brian, George and I finished up the runs on the hill just before lunch. Our tap count stands at 152 on 3/16” lines, and we’ll add another 25 on buckets once the sap really starts to flow.

Our sugaring operation is tiny compared to many of the regions producers, but we take pride in our smaller scale. Many of the big operations are running gas powered vacuum pumps, whereas we rely on skinny tubing and a mountainside to produce our suction. Larger operations tend to run oil-fired evaporators as opposed to wood, which just seems sac religious to me. And plenty of sugar markers will increase the density of their sap using reverse osmosis before it even hits an evaporator pan, which is more energy efficient, but also not the same as cooking it down the entire way with heat. To put it simply, I’d rather make syrup sitting around a simple wood fired evaporator, then a series of pumps and reverse osmosis filters and an oil fired beast, and I’d rather visit and get syrup from an operation using the traditional techniques as well.

This years minimal snow, locked in by a thick crust, made travel in our sugarbush like walking on a steeply inclined pond that broke under foot (even with snowshoes) on two of every three steps. The vertical nature of our woods provides plenty of gravity for sap, but gravity doesn’t discriminate. Progress was loud as the crust crunched under our snowshoes, and awkward as each stumble threatened to send us tumbling.

A trip to the top of our sugarbush requires a climb of roughly 250 vertical feet of climbing. Our trail doesn’t do any switchbacks or have any other hiker friendly features to make it easier. It’s a leg burner. Our chosen technique is to hike to the top of a run— a 1000’ish foot length of tubing with 15 to 25 taps along it. From the top of a run, we hike our way down, drilling holes in each maple, placing the tap, and tapping it in gently. Following the line as it zigzags through the woods, we tap each maple and move on. Once a run is tapped and we reach the bottom we head back to the top to tap the next run.

There’s elements to sugaring that are a leisurely activity for me. Like fly fishing, mushroom foraging, or shed hunting its an excuse to be in the woods. Even when relaxing, I have a need to feel like I am still “doing.” Being in the woods, examining the trees and preparing the harvest their sweet rewards is my equivalent of a Sunday afternoon on the couch. And its a good way to get some exercise to prepare for sitting around the evaporator and watching sap boil for the month.

2021 Meat Orders

It’s that time of year. We are ready to start taking deposits for 2021 meat orders. Here is a link to our meat share price sheet for this year. If you have never ordered with us before, below is a bit more information about how things work. We require a deposit to reserve orders. For information on availability and payment options, send us an e-mail (dundeeridge@gmail.com).

Goat Shares

We are offering goat shares for the first time in 2021. We have been loving goat meat in our own meals, and are excited to finally be able to share. We price the goat shares by hanging weight. In 2020 our goats averaged 50-pound hanging weights and returned market cuts per goat averaged about 30 pounds. After you make a deposit, we will ask you to fill out a cut sheet to specify how you want your goat cut by the processor.

We find the goat meat to be as versatile as other red meats with a milder flavor than you’d expect, and no gaminess. The ground meat is excellent and can be used just like you use ground beef. We like the roasts slow-cooked and pulled (we use a crockpot). We find the chops and steaks to be similar to lamb.

If you’re not yet ready to try a goat share, we do have individual cuts and ground meat available. We will be post prices in the near future, so stay tuned.

Pork Shares

We sell pork shares by hanging weight. That is the weight of the animal after slaughter but before it has been processed into market cuts. Last year our average hanging weight per pig was 250 pounds. On average, 72-percent of the hanging weight is returned as market cuts.

Here you can look at an example pricing breakdown for purchasing a pork share. Keep in mind, the hanging weights and exact take-home of market cuts are estimated. Once you place a deposit we will ask you to fill out a cut sheet for the processor. Here you will specify how your share is cut by the butcher, for example, do you want hams or ham steaks, how thick you want your chops cut, or do you want your ground pork seasoned (if at all). We can provide some guidance if you are unsure. Here is an example of the cut sheet we’ve used for our personal pig the last few years.

The cut sheet can be intimidating to fill out the first time, but overall its is difficult to mess up. No mater what, you will be getting back yummy pork.

Chickens

We will be processing chickens four times this year. Pricing and dates are on the price sheet linked to above. After chickens are processed we freeze them and once they are frozen they are available for pickup. It is possible, but not ideal, to make arrangements to pick up processed chickens prior to freezing.

We take a lot of pride in our meat chickens. We raise Freedom Rangers which is a slower growing, more active and healthy bird than other breeds.

A few considerations: A full pig will take up about the same space as 3 or 4 cases of beer. You will need a chest freezer. We recommend chest freezers for all of our meats, as they are colder and provide better preservation than conventional refrigerator-freezers. If you have space in your conventional freezer, a few chickens or a little goat meat would do fine, but not if you are looking to stock up on our meat for the year.

Also, when we set the pork pickup date it is firm as we do not have the freezer space to hold all the meat. Please consider this if you are not local.

Fighting Beeches

Our farm began as a mountainside hardwood forest. The first tree I cut on the farm side of the road was a small beech with a U-shape bend in it— a perfect door handle for my woodshop door.

Five years later, I estimate that 99-percent of the trees we’ve cut have been beech. And not just because their whacky bends make nice door handles. They dominate our hill at the expense of other hardwoods, and the majority are diseased and as a result susceptible to failure. Fortunately, one other thing they are good for is firewood.

Beech trees are supposed to have steel-gray bark, smooth with only minor imperfections. Think of an elephant’s leg. Nowadays, model beech trees are few and far between. Most are covered in black scaly markings, the telltale sign of beech bark disease.

It’s a one-two punch — a tiny scale insect bores holes in the bark and a fungus marches in and infects the tree. These days, beeches in northern New England are all too likely to be small and stunted or to bear the ugly, puckered cankers that mark them as infected. Beech bark disease “causes significant mortality and defects in American beech,” write US Forest Service researchers David R. Houston and James T. O’Brien.

Northern Woodlands

In our woods, beech trees that snap mid trunk or shed large sprawling limbs, have damaged some of our best oaks and maples.

Sections of our woods are overrun by beech saplings. Sometimes only a few inches in diameter, but over 15 feet tall. The population is dense enough that it makes walking difficult, and blocks any light that would help promote other vegetation. Sporadically mixed in with these saplings are larger beech trunks, between a foot and two feet in diameter, but dead with the trunk snapped off 15 feet up.

There is a good chance these young, dense beech stands were caused by partial thinning in the past.

Partial cutting of forest stands, where some trees are harvested and many are left standing, can perpetuate a monoculture of beech in the understory. Because beech is shade tolerant and sprouts proliferate from the roots, shade from the remaining trees creates perfect conditions for dense stands of beech sprouts.

UNH Extension

But it’s the beech bark disease itself that is doing the most to help the beech become overabundant.

It seems counterintuitive, but the proliferation of beech trees started with beech bark disease. When the disease kills a tree, the root system generates multiple new saplings. In turn, those young trees become diseased, die, and spawn yet more doomed saplings. For forest managers, the beech’s ability to regenerate presents a major problem: cutting a diseased tree only makes the problem worse. “That tree’s going to send up six, ten, maybe twelve new trees,” Weiskittel says. “It’s kind of like a whack-a-mole situation.”

DownEast Magazine

This is where the goats step in. Beech seedlings and foliage are known to be less than desirable browse for moose and deer who favor maple, oak, and birch. This is another reason for the beech trees’ recent dominance. At first, we noticed the goats having similar tastes, but they have eventually taken a liking to beech. As their tastes evolved they learned how to push the saplings down with their chests to better reach the crowns. It’s our hope that this acquired taste for the beech will help prevent new growth caused by the side effects of our partial clearing and the bark disease.

After clearing areas of beech or next step will be to replace what we’ve cut with other more desirable trees— we have 25 sugar maple seedlings coming from the state nursery this spring. The biggest challenge with his strategy will be keeping the goats away from the trees we want while having them help keep away the ones we don’t. It’s all the more reason we want to expand our woodland pastures, to spread out impact and allow us to manage the trees. Good thing we are professional fence installers (Future Blog Post).

This all segues neatly into what we’ve been up to lately. The lack of snow has made working in the woods easy this winter. We’ve long had a goal of creating better access to the far corners of our land, and what started as simple thinning around our maple lines in December has evolved into the start of a woods road project. Our southwest property line has the easiest grade, blue square as opposed to double diamond, and we’ve found a route that manages to weave its way around our largest boulders, which means we’ll need an excavator and not truckloads of TNT. Step 1. has been clearing the trees, which conveniently have all been beeches.

So on most weekend days, and some evenings after work, we’ll pack up a sled full of gear; chain saw, ax, felling wedges, bar oil, gas cans, dry kindling, a propane torch, etc. and cut trees, drag brush, and light burn piles. Ellie has been keeping herself entertained by bouncing on log “horses” and pretending to be ski patrol, rescuing injured skiers in the sled. It’s fun winter work that will warm you up fast even on the coldest days.

The new woods road, which we will hopefully make good progress on over the summer, will allow us to move the animals even further back on our land, helping us spread out their impacts and rotate their grazing more efficiently.

Back to the beech trees, it is worth noting that a small percentage of beech trees are disease resistant. They are easy to see in our woods as they stand out with smooth, scale-free bark. Another sign of useful beech is bear claw markings. Bears will return annually to the trees that produce the best crops of beechnuts, another positive aspect of the tree. High in protein and an important food source for wildlife, our goats and pigs seek them out in the fall.

All this being said, we aren’t foresters and unfortunately for us, we don’t own enough acreage to qualify for NRCS grant funds for forestry management. If we owned 10 or more acres (instead of 9.6), federal funds would be available for us to work with a forester, install woods roads, and make other forest improvements. We’ve tried multiple avenues to expand our acreage, but so far have come up empty. Until then, we will continue to do our own research, and adapt our strategies to improve our woods, while also providing room for our animals to browse on the forest’s bounty.

Sources:

DownEast Magazine – Beech Trees Are Killing Maine’s Forests

Real World Examples of Managing Beech

UMaine News – Warm Winters Bad for Beeches

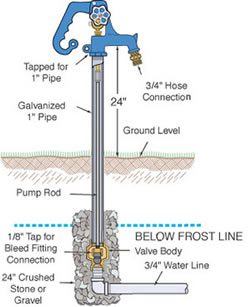

Farm Water in Winter

Doing the farm chores at 5:30 this morning, I portioned out sweet grain for the girls, slid a bowl of grain each for Mac and Murphy under their gate, and topped off the pig feeder with a 50-pound bag. Then, with the lift of a blue handle, I filled a 5-gallon bucket of water. One for the pigs, then another for the boys and another for the girls. It was -1 degree with a breeze, but the water flowed. The liquid miracle brought back memories of a September weekend filled with talcum powder soil dried out by a long summer drought when we redid our entire farm water system to make life easier when temperatures bottom out.

We’ve always had running water across the street for the animals. John Murphy’s old A-Frame had block lined dug well about 12′ deep. I had built a small insulated pump house to put over the top, and hung a heat lamp to keep the pump and pressure tank warm in the winter months. We’d fill buckets from a sillcock on the outside, and carry them to the animals twice a day. Aside from the joys of carrying heavy buckets up an icy slope, through a gate and across the barnyard, the system had other drawbacks as well. The warm pump house attracted rodents looking for a warm winter home. Mice and chipmunks would chew the insulation and leave other less-pleasant signs of there existence before ultimately meeting their fate in the drinking water below. We wouldn’t serve the water to a friend, and weren’t comfortable with it as a long-term solution for the animals either.

So we devised a plan. Around here, plans mean projects— expensive, difficult, time consuming projects that anyone without a farm would hire a professional to do. The goal is to make farm life easier in the longterm, but easier can be quite difficult in the short-term.

The plan in this case was as follows: move the pump and pressure tank to farm stand, feed it with a waterline coming from the well, then run waterlines from the farm stand to each of the animal areas; one up to the girls barnyard, one to the boys gate, and one outback to the pigs, which we’d be raising in the winter for the first time. All the waterlines had to be 5′ below ground to keep from freezing and connected to frost-free hydrants. Then, we’d do away with the old pump house and cap the dug well with a concrete lid to keep the rodents out.

The known challenges included digging in our boulder filled terrain along with getting the waterlines through the concrete foundation wall and up through the slab floor of the farmstead. Plus the overall scale; hundreds of feet of trench and waterlines, yards of boney soil to remove, tons of clean sand to backfill, truck fulls of drainage stone and 7′ tall hydrants installed 5′ below ground.

I stockpiled raw materials during the week leading up to project, and made multiple trips to the plumbing supply house to make sure we had everything we might need. I bought home an excavator after work on Friday (this is how we spend our weekends) and started to dig that night. By the end of the day Saturday the entire barnyard in every direction was either a 5′ deep trench, a 6′ tall mound of dirt or a pile of unearthed rocks ranging from the size of a basketball, to the size of a large trash barrel.

On Sunday Jeff, George (one person, and two) and Liz slung black poly pipe, and surrounded it gently with clean sand. They hooked up the yard hydrants and bedded them in drainage stone below ground. They tightened hose clamps, connected barb fittings and one of the, fell head first into a 6-foot deep trench. Brian piloted the tractor, spreading old fill this way and that while bringing back clean sand to backfill. Wayne relieved me in the excavator after lunch, and thrashed until the last trench was dug and filled well after dark.

In the following days, as the dust literally settled, I hooked up the pump system and water began to flow from the well, to the farmstead and out to the hydrants. And this morning, with windchills below zero in continued to flow, now clean and clear, straight to the animals. When it comes to the goats and chickens, the project made life easier—the girls drink about five-gallons per day, the boys a bit less. However, it made raising pigs in the winter possible. Even now, at about half the size they will become, the four pigs are going drinking close to 20-gallons per day. Hauling buckets any distance to their waterer wouldn’t have been practical. The project also made it so we could put a sink, and a frost free faucet in the Sugar House to help with cleanup during sugaring season.

The next trick is keeping the water from freezing once its too the animals. I’ll write about those strategies another time.

A few notes: We had some amazing helpers on this project. Some are mentioned above, others know who they are. Thanks to all. There was also a few side projects that happened at the same time: replacing all the below ground electrical wiring I inevitably dug up during the project, installing site drainage to help solve some water issues, and putting in a dry well.

Glad You Made It

Welcome to the Farm.

As Liz and I built this place over the last five-plus years, a few themes kept coming up.

“We’re crazy.”

” Can we call this place a farm?”

“Will the projects ever end?”

“Keith should be writing about this.”

True. Yes. No. And how do you expect me to have time for that? But alas, here I am. Stars aligned, animals behaved, we ran out of shows to binge on Netflix, I found some help building a website (Thank Ty!)

I used to be a bit of a writer. I had long hair, an apartment to myself, and way more free time than I realized. Of course, life got busy; an adventurous girlfriend turned wife, a property to transform, pigs to catch, and a daughter to adore all happily pulled me away from the keyboard, but all along, I knew the times racing by would make the best stories.

There’s story of Liz helping Trevor Limmer skin one of our pigs with toddler Ellie in a backpack and me on the sideline with a severe hand injury. Or the story of writing a cold letter to buy an abandoned lot with a falling down barn and burnt down house, then cleaning it all up and rebuilding the barn in time for our wedding 5 months later. The story of Crazy Boy the goat kid. Or the story of Liz and I, pre Ellie, breaking through ice on Allagash Lake in early May, and paddling an overflowing Allagash stream at the start of our first trip down the Allagash.

They’d all have made great stories, but I felt like if I was writing, I wasn’t doing. I’d lay in bed and write the stories in my head, but they’d be written over the next day, and again the next.

So here I will write. Maybe a sunrise glow during morning chores will be an inspiration for words. Maybe I’ll write about knocking a valve stem off a loaded tractor tire and the costly repair we call our tuition (Thanks Wayne). Someday I will hopefully write about an epic canoe adventure down the spring snowmelt waters of the St. John River in Northern Maine. I could write summaries of goat kidding seasons, reflections on the recent pork crop, or a how-to on chicken butchering. Maybe a review of an indispensable tool we use on the farm. There are two sure things; I’ll definitely promote our products, and post way too many pictures of Ellie.

So check back, stop by, ask questions and slow down on Dundee!